Penguins

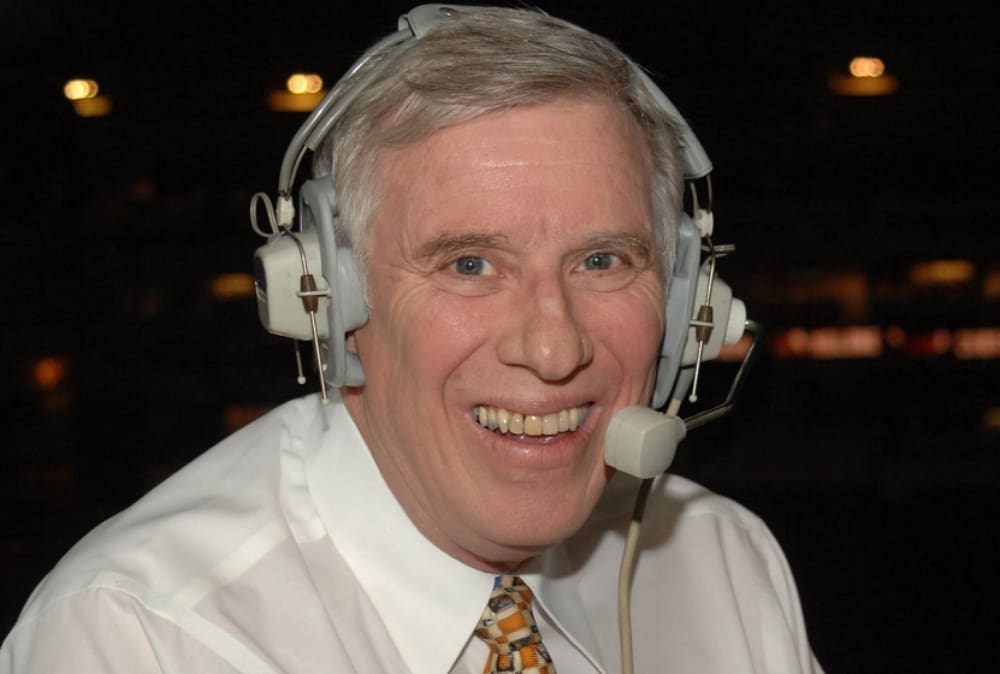

Molinari: Remembering Mike Lange, You Had to Be Here to Believe It

Mike Lange was a big fan of Miller Lite.

He liked the blues even more.

But he flat-out loved hockey, and when he was able to blend those three — like, say, on Penguins road trips — well, it didn’t get much better than that.

Even as Lange enjoyed immersing himself in his music of choice — whether the artist was Son Seals or Sunnyland Slim or Buddy Guy or anyone else — he was never truly off the job. At least one of his beloved catchphrases, “She wants to sell my monkey,” was lifted directly from a blues song of that title in the early ’90s after he and a traveling companion heard it performed at one of the many blues clubs he frequented in Chicago.

Lange could have sniffed out a good blues joint in a town where livestock outnumbered humans, but there was no need for nighttime sleuthing when the Penguins visited Chicago. He didn’t need to ask directions to his favorite haunts, like Blue Chicago and Kingston Mines, and when he’d had his evening’s fill of music, he’d head back to the team hotel.

Usually, there would be a stop along the way for an oversized, deep-dish pizza that he and his sidekick came to know as “manhole covers.” (That was a reference to the size and weight, not the texture, of the pizza.)

You know how some men maintain a “little black book” to keep track of women with whom they’ve been romantically involved? Well, Lange had one of those, too, except his detailed the best places to eat in every NHL city and the best dishes a particular place offered, whether the food was to be consumed well before a game or long after-hours.

His catchphrases — from “He’s smiling like a butcher’s dog” to “Buy Sam a drink and get his dog one, too” to “He didn’t know whether to cry or wind his watch” — helped to make Lange, who died Wednesday at age 76, one of the most beloved figures in Penguins history. But he also had a gift for connecting with people, even if he never actually met them.

Just how popular was Lange with the hockey community in Pittsburgh? Here’s one bit of evidence: In the first half-hour after PHN posted a story about his passing Wednesday night, a social media post with a link to the story drew 460 likes and 190 re-posts. Most stories are fortunate to get 10 — no, five — percent of that kind of attention on social media, even if they include a link to a secret Swiss bank account.

For Lange, the outpouring of grief and love and appreciation from those who learned hockey — and learned to love it — from him was just beginning. By midnight, those totals had swollen to 421 and 1,300-plus, respectively.

Although Lange never played the game — hey, he grew up in Sacramento, which was not a spawning ground for hockey players when he was a young man — he had an instinct for it that even some players couldn’t match. He often was able to sense when a goal was about to be scored at either end of the ice several seconds before it actually happened.

Lange not only could describe how a sequence on the ice was unfolding, but routinely gave listeners and viewers a feel for where it was headed. That’s part of the reason several generations of fans say they were taught the game by his broadcasts; he didn’t just explain what was happening, but why it was. And what might happen next.

Lange’s exceptional feel for hockey was just one facet of his success. The time and effort he invested in obtaining information that he would present to the public also was a big part of it.

He would spend a few hours before each game researching and compiling notes that might be used during the broadcast, even if he had to do it in a place like the press room at the Met Center in Bloomington, Minn., where it sometimes seemed the only illumination was coming from a 10-watt bulb dangling from the ceiling.

Lange was known to many of his friends — and a lot of people who never actually met him, but felt like they had a long-standing relationship — as “Mikey.” The name was a perfect fit: Casual and friendly, much like the man himself.

Being able to transmit his personable nature into radios and TVs across Western Pennsylvania and beyond helped to attract fans to his broadcasts, even when the Penguins’ on-ice performances seemed designed to chase them away. And he kept those people interested in hockey by entertaining them with his creativity and teaching them with his knowledge. He could make even the most pedestrian games seem special.

His commitment to the audience — the people who respected, or even revered, him — never waned. When his career was winding down and medical issues robbed him of his mobility, Lange got around the hallway in the PPG Paints Arena press box — or, as it officially is known, the Mike Lange Media Level — on an electric scooter.

It wasn’t quite the same as the land yacht he used to get around the region when he was a younger man, but Lange made it work.

Lange’s warmth and insights helped to make him one of the legendary voices in the sport, a worthy peer to the venerable likes of Dan Kelly and Fred Cusick and Danny Gallivan and so many of his fellow recipients of the Foster Hewitt Award, which comes from the Hockey Hall of Fame and honors hockey broadcasters who “made outstanding contributions to their profession.”

Lange did all of that and so much more. No one in an off-ice role did more for the Penguins than Lange, and only a couple of players — the list begins with Mario Lemieux and ends with Sidney Crosby — had an impact rivaling his.

Fact is, if Mike Lange had never come to Pittsburgh, the Penguins might not be here today. When the heartbeat of the franchise was faint in the pre-Lemieux days, he gave people reason to pay attention to them.

Which, in turn, helped to convince owners not to act on offers to transfer the franchise to outposts like Kansas City or Hamilton, Ontario.

So this might be a good day for those he taught so much, for so long, to hoist a Miller Lite and chomp down on a manhole cover in Mike Lange’s honor. And while you’re at it, take care of Sam and his dog, too.